How many people today have left the Church because they deem the Bible incongruent, mythological and unscientific? This falling away is usually undergirded, whether knowingly or unknowingly, by assumptions made in critical historical and textual analysis of the Bible. Modern scholars have sought over the past couple of centuries to deconstruct the Bible by weeding out prophecies, miracles, supernatural occurrences, and other textual peculiarities from the “historical facts.” This technique of Biblical criticism has been used to try to delegitimize Jesus in the New Testament and Yahweh in the Old Testament. What we are left with, so they say, is that we know little about the “historical Jesus,” if he even existed, and much less about the genocidal, tribal God of the Hebrews.

This is exactly the type of heresy that St. Polycarp fought against in the 1st and 2nd centuries.

St. Polycarp, as one of the prime Apostolic Fathers, had direct contact with St. John and the other Apostles. He had one degree of separation from Jesus. Polycarp himself was a direct disciple of St. John the Apostle. St. Irenaeus, who was a student of Polycarp, wrote in Against Heresies that Polycarp “was not only instructed by the Apostles, and conversed with many who had seen the Lord, but was also appointed bishop by Apostles in Asia and in the church in Smyrna.” He also wrote reminiscently about Polycarp in his letter to Florinus, “I seem to hear him now relate how he conversed with John and many others who had seen Jesus Christ, the words he had heard from their mouths.”

One of the stories that Irenaeus heard from Polycarp was about a time when St. John was in Ephesus. He describes seeing St. John going to take a bath, but upon seeing Cerinthus [a Gnostic heretic] inside the building, he rushed out saying, “Let us get out of here, for fear the place falls in, now that Cerinthus, the enemy of truth, is inside!” Along these same lines, Polycarp himself ran into on one occasion a similar heretic, Marcion. Marcion said to Polycarp, “Don’t you recognize me?” To which Polycarp responded, “I do indeed: I recognize the firstborn of Satan!”

Marcion was a well-known heretic of his day. He espoused a particular semi-gnostic heresy that the God of the Old Testament could not be the God of the New Testament and Jesus. There were “two gods,” or so he thought, in a dualistic world. The Old Testament God was the Demiurge creator of the material universe, who sought to impose legalistic justice with harsh and severe punishments; while, the God of the New Testament gospel was one of kindness, compassion, and mercy. As he found these two dichotomies irreconcilable, Marcion dismissed all of the Old Testament and much of the New. Marcion was, in effect, the first Bible critic.

St. Polycarp was not amused. The early Church historian, Eusebius, records Irenaeus’ account of how St. Polycarp would react to the Gnostics he encountered, saying, “O good God! For what times hast thou kept me that I should endure such things!” Although Marcion did believe in the divinity of Jesus, he was a Docetist, who believed Jesus only had an imitation body. In effect, he denied the physical birth, death and resurrection of Jesus. Polycarp responded by quoting St. John, “To deny that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is to be Antichrist.” Marcion distorted Paul’s theology to create an all-forgiving God, and rejected the hard-sayings of the Gospels and the so-called wrathful, jealous God of the Judaism.

Many modernist critics today (i.e., atheists, agnostics, universalists, etc.) agree with Marcion’s interpretation of Scripture. Marcion’s influence from the 2nd century seems to have extended all the way to the 21st century. This modernist attack on the veracity of the Scriptures has certainly contributed to the “rise of the nones” (i.e., those who increasingly espouse “none” as their religious affiliation). They deny that sacred Scripture is the inspired work of the Holy Spirit, and see it rather as the work of fallible men alone. This watered-down version of the faith has even crept into some Christian circles as well. Their mantra is “Jesus is love,” so how could he also be a God of justice?

Interestingly, Marcion’s heresy forced the young Church to deal rather quickly with this challenge to Scripture by assembling and defining the canon, which would eventually take on the form of the modern Bible. St. Polycarp may very well have been one of those early Church leaders who helped define the canon. Polycarp’s own writing “The Epistle to the Philippians” was ultimately not included in the canon of Scripture, but it gives us great insight into the mind and heart of an Apostolic Father who interacted directly with St. John the Apostle.

St. Polycarp is perhaps most well-known for his martyrdom, which happened probably on February 23, 155 A. D. This is now the day we celebrate his Feast day, or, as the account of his Martyrdom refers to it “the birthday of his martyrdom.” “The Martyrdom of Polycarp” is also the first recorded martyrdom themed letter after the New Testament period. It follows a particular genre highlighting the similarities in Polycarp’s death with the Passion and Crucifixion of Christ.

By this time in 155 A.D., Polycarp was an old man in the midst of a repressive pagan, anti-Christian Roman Empire. The Empire was forcing all to publicly offer incense and declare that Caesar is Lord. Those who did not were killed, and in the most barbaric ways, such as being thrown to the wild beasts in the arena. Christians were a prime target as many refused to apostatize.

Three days before his arrest, Polycarp had a vision of “flames reducing his pillow to ashes.” Whereupon Polycarp turned to his companions and said, “I must be going to be burned alive.” When the Romans finally seized him, he said peacefully “God’s will be done.” Then, they brought him to the arena with “deafening clamor” full of pagans who wanted to kill him.

It was then that “a voice from heaven” was heard. Here follows a few excerpts of his martyrdom:

“As Polycarp stepped into the arena there came a voice from heaven, ‘Be strong, Polycarp, and play the man.'”

Polycarp is then brought before the proconsul for examination. He tells Polycarp: “Take the oath, and I will let you go,” and “Revile your Christ.”

Polycarp’s response is, “Eighty six years have I served Him, and He has done me no wrong. How then can I blaspheme my King and my Savior?”

The proconsul tells him, “I have wild beasts here. Unless you change your mind, I shall have you thrown to them.”

Polycarp declines again, to which the proconsul says, “If you do not recant, I will have you burnt to death, since you think so lightly of the wild beasts.”

Polycarp rejoined, “The fire you threaten me with cannot go on burning for very long; after a while it goes out. But what you are unaware of are the flames of future judgment and everlasting torment which are in store for the ungodly. Why do you go on wasting your time? Bring out whatever you have a mind to.”

Upon that, they bind Polycarp to a pile of wood to be burned alive “like a noble ram taken out of some great flock for sacrifice: a goodly burnt-offering all ready for God.”

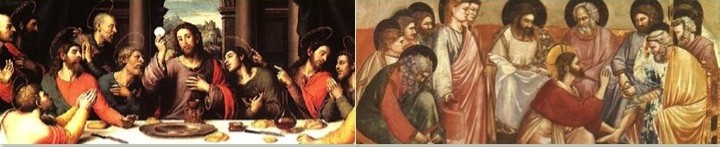

Polycarp proceeds to give his final prayer, offering himself up as a Eucharistic sacrifice in union with the sacrifice of Christ. In part, praying, “I bless thee for granting me this day and hour, that I may be numbered amongst the martyrs, to share the cup of thine Anointed and rise again unto life everlasting, both in body and soul, in the immortality of the Holy Spirit.”

With that, the fire is lit and “a great sheet of flame blazed out.” Then, another miracle occurs. The author writes, “we who were privileged to witness it saw a wondrous sight . . . the fire took on the shape of a hallow chamber, like a ship’s sail when the wind fills it, and formed a wall round the martyr’s figure; and there was he in the center of it, not like a human being in flames but like a loaf baking in the oven.” Again, he depicts Polycarp’s martyrdom in Eucharistic terms “like a loaf baking.” They then smell “a delicious fragrance.”

His martyrdom concludes with this:

“Finally, when they realized that his body could not be destroyed by fire, the ruffians ordered one of the dagger-men to go up and stab him with his weapon. As he did so, there flew out a dove, together with such a copious rush of blood that the flames were extinguished; and this filled all the spectators with awe, to see the greatness of the difference that separates unbelievers from the elect of God. Of these last, the wondrous martyr Polycarp was most surely one.” The account comes to a close with the author stating the martyrdom of Polycarp the Blessed is “talked of everywhere, even in heathen circles. Not only was he a famous Doctor, he was a martyr without peer.”

Saint Polycarp offers us an example this Lent. He was a great Apostolic Father who adhered steadfastly to orthodoxy and fought against heresy and Gnosticism. He had a simple but strong faith, and spoke in Eucharistic terms of self-sacrifice. His self-denial led him eventually to his own martyrdom. This Lent we also walk the way of the Cross, in a self-sacrificial union with Christ. We mortify our bodies in Lent with the hope to rise in our bodies with Christ in Easter.