“When the sense of God is lost, there is also a tendency to lose the sense of man, of his dignity and his life.” (Evangelium Vitae, 21)

It is a perplexing fact of history that one of the world’s most prolific mass murderers, Adolf Hitler, was also a vegetarian who abhorred cruelty to animals. This conundrum was oddly revisited when People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) ran a publicity campaign “Holocaust on Your Plate” in 2003 comparing caged farm animals to Jewish prisoners in Nazi death camps. As author Richard Weikart points out, ironically both the Nazis and PETA engaged in the fallacy of anthropomorphism, blurring the distinction between humans and animals. These are extreme examples, but highlight an underlying philosophical confusion in our modern era regarding the dignity of human life. Subsumed in this diminishment of human worth is an implicit denial of personhood.

This misanthropic view is unfortunately on the ascendancy in Western culture. To have a sense of this, one need only look at the recent outpourings of indignation and contempt at the killings of Cecil the lion and Harambe the gorilla. The flipside of overvaluing animal life can often be the devaluing of human life; the outrage over Cecil and Harambe stand in stark contrast to our culture’s complacency regarding abortion, euthanasia, eugenics, suicide and assisted-suicide. This “culture of death” is the negative underbelly of the modernist endeavor: recasting the human being as simply an ordinary animal who no longer merits ontological God-given dignity or teleological God-given purpose. Human life becomes expendable compared to the perceived greater good of the society or state, or the whimsy of the individual. The worth of the human person today has become obscured.

How did we get here?

Conflating the dignity of man and animal is but a symptom of the overall creeping confusion. A dimming appreciation for the specialness of man runs centuries deep, with incremental philosophical subversions to the foundations of true knowledge.

At its core, we are in a crisis of epistemology. The great breadth and depth of human knowledge have been sacrificed on the altars of skepticism and materialism. This modern epistemological error revolves around the denial of our true human nature as composite beings, of body and soul. The initial missteps of severing body and soul were philosophical.

Some trace the errors of modern secularism back to William of Ockham in the 14th century, who posited that universal essences, like humanity, are not real, but are only nominal extrapolations in our minds. Ockham theorized there are no universal forms but only individuals. This undermined part of our ability to explain objective reality. If there is no universal human form, or human nature, then we are deprived of fulfilling those ends of our nature and our teleological purpose. Once that is gone, it is not hard to imagine a confusion of personhood and a loss of ethics.

In the Enlightenment era, empiricists, like Locke and Hume, proposed that only the phenomenon of a thing could be known, and not the thing itself. Like Ockham, they rejected abstract knowledge of universals in favor of sense experience only. In other words, they dismissed our intellectual and spiritual knowledge for something akin to that of animals. Kant similarly conceded that we only know “things as known,” as interpreted by the mind, but not “things in themselves.” This “epistemological geocentrism,” as physicist Father Stanley Jaki called it, prevents us from having knowledge of God, the soul, and the full nature of reality.

Perhaps the most damaging blow to our understanding of our composite natures comes from biological materialism, in the form of Darwinism in the 19th century. Darwinian theory made strict biological materialism and scientism the predominant “acceptable” knowledge. No longer was there a need for the special creation of man by God, or the need for an immaterial soul or intellect. Man is just an evolved ape, created through blind forces, genetic mistakes, and the survival of the fittest. The severance of body and soul, begun in the philosophies of the previous centuries, was now complete. As Chesterton noted, “Evolution does not especially deny the existence of God; what it does deny is the existence of man.” Man was no longer a composite spiritual being, but mere physical creature.

This materialist reductionism had major repercussions on the modernist worldview and the dehumanizing of man. When the materialists finally seized power, Communist regimes, from Stalin to Mao to Pol Pot, murdered some 100 million people. Social Darwinism too had seeped into Western thought, sparking talk of people as “fit” and “unfit,” and races as “superior” and “inferior.” This was most pronounced in Nazi Germany, where racist notions were “proven” and “justified” by so-called science. Hitler had fully embraced this idea of evolutionary ethics in his march towards war and genocide.

The evidence of the past century has highlighted the fact that evolutionary ethics is no ethic at all. It undermines our moralistic certainty. Morality becomes very subjective, and in the spirit of the age, relativistic. Material reductionism altered people’s view on the sanctity of human life, by devaluing what it means to be human. The soul became merely an epiphenomenon of matter. In that sense, Christianity is at odds with strict Darwinian materialism, as opposed to the general theory of evolution, with which there is no conflict. This dogmatic materialism denies a priori even the possibility of final causality in man. It falsely stifles the reasonableness of belief in God, our moral compasses, and the knowledge of our selves as spiritual beings.

Sadly, this epistemological reductionism has not only persisted to the present day, but also increased. Although there is some progress against the culture of death, there remains a peculiar amnesia regarding the dignity of man, lingering in our cultural psyche. Not surprisingly, there has also been a concurrent falling away from the faith, as evidenced by record numbers of non-religious and atheists in recent polls (i.e., the “rise of the Nones,” so-called for listing “none” as their religious preference).

How are we as Catholics to respond? To start, we can reaffirm that there are many good, intellectual, and multifaceted reasons to believe. Christianity and belief in God are perfectly reasonable, despite protestations from modern scientific materialists and atheists. Science and theology, faith and reason are not opposed to each other, but are “like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.” (Fides et Ratio) In fact, there is available today more cutting-edge scientific data suggesting a Creator than ever before. What better confirmation is there, for example, of Aquinas’ cosmological argument for God as the prime mover than the Big Bang and the latest supporting evidence of cosmic microwave background radiation?

Christianity was built upon revelation, of course, but also upon reason. Jesus had commanded us to love God with “all your mind.” (Mt. 22:37) The intellectual tradition of the West, and its empirical science, is, after all, borne out of Christian civilization. The contention with modern secularism only arises with the materialist denial of God and the soul. It is a denial of our composite being. Atheism suffers from an epistemological defect of rejecting personhood. As Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum states, “It is the mind, or reason, . . . which renders a human being human, and distinguishes him essentially from the brute.” We should embrace the idea of personhood and the philosophy of personalism as part of our worldview and ethic, and as a bulwark against dehumanizing philosophies.

One of the greatest proponents of the modern philosophy of personalism was Pope John Paul II. Pope John Paul, then Karol Wojtyla, witnessed these dehumanizing forces of materialism firsthand in Poland, initially under Nazi occupation, and later under Soviet Communism. He was in the epicenter for both of these totalitarian outbursts, and observed what he called the “pulverization” of the human person. It was in reaction to these impersonalist philosophies and the subsequent political tyrannies that he helped lead a new philosophical movement and moral theology focused on the absolute dignity of the human person.

Wojtyla advocated for “Thomistic personalism,” a modern philosophy focused on the transcendent dignity of each person. His particular personalism was grounded in Thomas Aquinas’ classical metaphysics, and the cosmological view of man that we are set apart from the rest of creation by our rational nature and intellect.

Wojtyla sought to go beyond this, however, to explain the “totality of the person.” He recognized the great importance of the interior perspective to human experience. This interior perspective he referred to as “subjectivity,” experienced in each person’s consciousness, where no two are alike. Each person, then, is utterly unrepeatable, irreplaceable, incommunicable, and irreducible.

Pope John Paul spoke of this in practical terms, in his “personalist principle,” that the human being should always be treated as an end in itself, and never subordinated to another as a means to an end. Internalizing this principle would inevitably produce concrete practical applications, such as standing against slavery and human trafficking. But, it could also help turn the societal tide against normalizing this culture of death, with its impersonalist impulses, as recently witnessed in the Netherlands, euthanizing a man for being an alcoholic, or with Peter Singer, a utilitarian ethicist from Princeton, advocating for ending the lives of severely disabled infants.

As Catholics, we must always advocate for the inviolable dignity of the human person. This, of course, goes all the way back to Genesis when “God created man in His own image.” (Gen. 1:27) The magisterium echoes this by calling each of us “a sign of the living God, an icon of Jesus Christ.” (EV, 84) We have an interior transcendence in common with our Creator. Humans are relational and social beings, made in conformity to God, a trinity of intra-relational Persons.

As the image of God, there is a specialness to man. It sets us apart from the rest of creation. We alone can say “I.” No other animal, as wonderful as they are, can utter such a thing. They are bound by instinct. Even in the higher primates, as with the fascinating case of Koko the signing gorilla, the disparity remains immense. In the words of Pope John Paul, “an ontological leap” has to be made to span the “great gulf” that separates person from non-person. Man alone is capable of rational and abstract thought, free will, self-consciousness, moral action, complex language and speech, technological progress, higher purpose, altruism, love, creativity, prayer and worship. Man is different in degree and in kind, because God makes each person from the infiniteness of Himself. (CCC 2258)

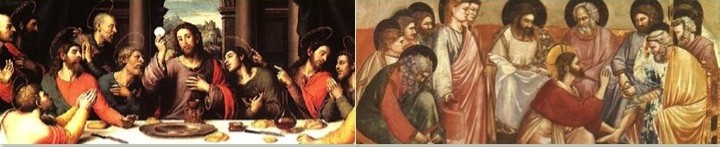

In the New Testament, Jesus gives us the heart of personalism with His commandment to “love your neighbor as yourself.” For, as He later reveals, “as you did it to one of the least of these My brethren, you did it to Me.” By embracing this notion of personalism in our lives, we liberate ourselves from our own egoism and coldness towards our neighbor. We see the face of God in each other. This is our vaccination against dehumanizing a person, and adopting a culture of life. It stands against the slide of centuries towards extreme skepticism and materialism, and calls us to draw again from a more complete knowledge. Materialism is only partially true. It denies the higher nature of our spiritual selves. By recognizing the image of God in each other we see the universal ontological value of each person, even down to the seemingly lowliest and weakest among us. It is for us to contemplate (and act upon), in light of Christ’s sacrifice, “how precious man is in God’s eyes and how priceless the value of his life” with “the almost divine dignity of every human being.” (EV, 25)