Saint John tells us in the Book of Revelation “when the Lamb opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven for about half an hour.” (Rev. 8:1) The silence of heaven rests above the great din of the world. Before the immensity of the Infinite, there are no words, only wonder, adoration, and silence. We have a foretaste of this eternal silence in the Divine Liturgy, which is the liturgy of the Church. Rivers of living water and sanctifying grace flow not only about the heavenly Throne, but also into the sacramental confines of hearts and flesh. Yet, as Cardinal Sarah says in his book The Power of Silence, if we, who are made in the image of God, are to approach him, “the great Silent One,” we must first quiet ourselves and enter into his silence.

But, the world today is raging against the silence of eternity. “Modern society,” Cardinal Sarah tells us, “can no longer do without the dictatorship of noise.” Postmodern man engages with hellish noise in “an ongoing offense and aggression against the divine silence.” Humanity has lost its sense of sin, and no longer tolerates the silence of God. He poignantly describes the current sad state of man: “He gets drunk on all sorts of noises so as to forget who he is. Postmodern man seeks to anesthetize his own atheism.” Even within the Church there is a noisy undercurrent of idolatrous activism. In this wonderfully written book with so many striking passages, the African Cardinal seeks to re-proselytize the increasingly secularized and debased West; the new evangelization rises from south to north.

Why silence? Silence is the chief means that enables a spirit of prayer. “Developing a taste for prayer,” he confides, “is probably the first and foremost battle of our age.” In modern techno-parlance, if our “interior cell phone” is always busy, how can God “call us”? Without silence, there is no prayer; and without prayer, there is no supernatural life in God.

Silence is not necessarily not speaking, but rather, it is an interior condition of the soul. “God is a reality,” he tells us, “that is profoundly interior to man.” God resides within the heart of man. The path to God is a path of interiority. At the Carthusian monastery of La Grande Chartreux in the French Alps, where they observe the vow of silence, interiority is a way of life. But, as wonderful and as holy as an exterior vow of silence is, it is not really an option for most people. Most lay people live amidst of the noise of the world. Cardinal Sarah understands this, and recommends a solution: “each person ought to create and build for himself an interior cloister, a ‘wall and bulwark’, a private desert, so as to meet God there in solitude and silence.” Man must learn to live in an interior silence, ‘an interior cloister,’ which we can bring with us wherever we go.

This silent interiority lends itself to a sacramental vision of the world. The silent and invisible Spirit of God dwells within the physicality of our bodies. We are a temple of God. Cardinal Sarah tells us that God gave us three mysteries to sanctify and grow our interior life with Jesus, namely: the Cross, the Host, and the Virgin. We are to contemplate these continually in silence. They are incarnational and sacramental by nature, where the heavenly is mingled with the mundane, and the divine lies hidden within the ordinary. So it is with our interior cloister, where the divine comes to rest silently in our human nature. In this sacramental vision of reality we participate directly in the mystery of God and impart it to the world.

Our primary focus should always return to the silence of Jesus. The divine silence entered the world as the “all-powerful word leaped from heaven”(Wis. 18:14-16) to be conceived and born of a woman, the Virgin. Mary is nearly silent in scripture, though she echoes over the ages “Do whatever he tells you.” Few words are recorded from the Holy Family, including not one word from St. Joseph, his silence reflecting his saintliness. Divine silence and humility came first as a baby in Bethlehem. Cardinal Sarah reminds us of this first scandal, “God hid himself behind the face of a little infant.” No stage of human life is deemed unworthy of Christ.

Then, for thirty years Jesus lived a hidden and silent life in Nazareth. So much so that his neighbors question at the beginning of his public ministry “where did this man get all this?” His divinity was veiled in everyday life, even though his mission of redemption had already begun from the ordinary woodworking in the carpenter’s shop to the mundane sweeping of its floors. Our interior silence is of upmost importance because it allows us to imitate the Son of God’s thirty years of silence in Nazareth. Jesus recapitulated within his “holy and sanctifying humanity” all the ordinariness of our human natures and vocations. By doing so, “the hidden life at Nazareth allows everyone to enter into fellowship with Jesus by the most ordinary events of daily life.” (CCC 533) Our interior cloister should be animated with the knowledge that, no matter where we are or what we are doing, Christ is there with us in the silence of Nazareth.

In the Cross, Cardinal Sarah reminds us that “the mystery of evil, the mystery of suffering, and the mystery of silence are intimately connected.” This trinity of mysteries is summed up in Jesus’ cry from the Cross quoting Psalm 22, “My God, my God why hast thou forsaken me?” Modern man likes to see the silence of God in the face of horrible, tragic events as proof of his non-existence: “if evil and suffering exist, there can be no God.” Yet, as Cardinal Sarah points out, the infinite and absolute love of God does not impose itself on anyone: “his respect and his tact disconcert us. Precisely because he is present everywhere, he hides himself all the more carefully so as not to impose himself.” In creating man and the world, God had to, in effect, “withdrawal into himself so that man can exist.” In allowing for human freedom and freewill, God would necessarily appear silent.

Man’s freedom, and ultimately sin, would leave God disappointed in man, and make God himself vulnerable to suffering, as a Father suffers for his child. The suffering of man leads to the suffering of God. God is with us in our suffering. The mystery of suffering and God’s silence will never be fully understood in this life, but must be viewed from the lens of eternity. God’s time is not like our own where “a thousand years are like one day.” Our brief sufferings on earth disappear forever like drops of water into the immense ocean of eternity. Even now, the person who prays often can “grasp the silent signs of affection that God sends him” as noticeable only by those who are lovers. Jesus has revealed, however, that bearing our crosses and silent sufferings can be redemptive and sanctifying. We can complete what is “lacking in Christ’s afflictions” for the sake of the Church. Our interior cloister should be united with the redemptive sufferings of Christ in his Passion and Crucifixion.

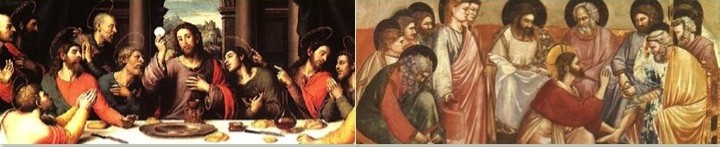

Jesus remains with us now, most silent and most humble and most small in the Eucharist. As the bread and wine become the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ, “the miracle of transubstantiation comes about imperceptibly, like all the greatest works of God.” There is no extravagant burst of light and power at each Eucharistic consecration, only silence before the Real Presence of God in the Host and the Mass. Cardinal Sarah laments the lack of silence and adoration today in much of the modern liturgy, declaring bluntly “The liturgy is sick.” He continues: “The liturgy today exhibits a sort of secularization that aims to ban the liturgical sign par excellence: silence.” Rather, reception of Holy Communion should be a moment of intimacy with the Lord, when we “receive the Lord of the Universe in the depths of our hearts!” Our interior cloister should be continually fortified by the words of Jesus: “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him.” (Jn. 6:56)

In every manner in every mode of everyday life, silence is necessary. Silence is necessary because it predisposes us to a life of prayer, a life of interiority and a sacramental vision of reality. Through the seven sacraments, the channels of dispensation of the divine grace of Jesus Christ to the world, we are recapitulated within Christ – a holy priesthood making spiritual sacrifices. We are spiritualized and divinized, made into children of God. Jesus adjures us not to leave the way of the sacramental life, for “apart from me you can do nothing.” Our prayers and sacrifices are “like the fragrance of incense that ascends to God’s Throne.” Each of us can become, as Saint John Paul called, a “contemplative in action.” Our practice in the virtues of silence and prayer are “an apprenticeship in what the citizens of heaven will experience eternally.”

Silence is needed most urgently now, even for those in the Church who would subsume social activism ahead of the worship of God. Cardinal Sarah proposes “a spiritual pedagogy” as illustrated by Mary and Martha in the gospel. Jesus does not rebuke Martha for being busy in the kitchen, but rather for “her inattentive interior attitude” towards Christ, as shown in her complaint about the “silence” of Mary. Mary remained at the feet of Jesus in silent contemplation and adoration. Cardinal Sarah warns, “All activity must be preceded by an intense life of prayer, contemplation, seeking and listening to God’s will.” We should be Mary before becoming Martha. Man can encounter God only in interior silence. The active life must be harmonized with the contemplative life. Silence must precede activity.

Silence is a form of resistance to the noise of the world. There is a danger today of being lost in “unbridled activism,” where our interior attitudes are diverted from Jesus towards social justice and politics. In the field hospital of the Church, the social aspect does have its place, but as Cardinal Sarah says, “the salvation of souls is more important than any other work.” This vital effort entails evangelization, prayer, faith, repentance, mortification and embracing the sacramental life, in short, living a liturgical existence. Before venturing out into the noise of the world, Cardinal Sarah’s The Power of Silence encourages us to remain firmly grounded in our interior cloister, adoring God in silence.