Advent is a good time to meditate upon the central role of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the conception and nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ, that is, the central role of Mary in our redemption.

As Marino Restrepo was being held hostage for six months in 1997 by Columbian FARC rebels and near death, he had a great mystical experience of the Lord Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary. In his testimony, he describes a vision of the Virgin Mary to whom he was united by “a spiritual umbilical cord.” He further testifies to her centrality: “Everything that I was receiving from Heaven went through her first. Similarly, everything that emerged from my heart and moved towards Heaven passed through her.” Mr. Restrepo experienced what the Catechism calls the “motherhood of Mary in the order of grace” as the “Mediatrix.” (CCC no. 969; Lumen Gentium 62) That is, the sanctifying grace of Jesus Christ is distributed to us through the intercession and mediation of the Virgin Mary.

We see this in the Incarnation. God willed for the Son not to be manifested directly, but to be born through Mary. God the Creator manifests himself through the intermediary of his creature. The Holy Spirit overshadowed Mary and she conceived Jesus and nourished his body through a physical umbilical cord. When the Holy Spirit comes upon us in faith and the sacraments, spiritual nourishment is given to us as the Mystical Body of Christ. Mary is the spouse of the Holy Spirit, who produces the Mystical Body of Christ in each soul by way of a spiritual umbilical cord. Jesus attests to this spiritual conception and birth: “That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit.” (Jn. 3:6) The Virgin Mary is literally our spiritual mother by order of grace to those who are the children of God.

St. Louis de Montfort speaks of the important intercession and mediation of the Virgin Mary as seen in the typology of Rebekah, the wife of Isaac, in the Old Testament. In the Book of Genesis, Jacob, the younger son, claims the blessing his father Isaac, and all the inheritance that entails, rather than the rightful inheritor, the first-born son Esau. Jacob puts on the garments of Esau and tricks the father Isaac into blessing him instead. These are typologies for Christ and us. Esau, as the first-born son of the father, and rightful inheritor of the father’s blessing, is a typology of Christ, the first-born Son of God the Father. Jacob, on the other hand, as the younger son, who puts on the garments of Esau, and receives the blessing of the father, is a typology for us, as Christians. We are not worthy of receiving the blessing of God the Father and his inheritance, but only through “putting on Christ” (Gal. 3:27; Rom. 13:14) are we blessed by God the Father and receive the inheritance of eternal life. By putting on Christ in Baptism and the sacraments, we receive Christ’s “white garments”of sanctifying grace of purity and righteousness (Rev. 3:18). This is the idea of substitution found through the Old Testament that the younger son receives the merits due to the first-born. This finds its fulfillment in the New Testament where Christ the first-born Son’s garments are given to us. Our unworthiness is substituted with Christ’s worthiness.

The typologies found in Genesis with Jacob, Esau, and Isaac extend to Rebekah too. It is Rebekah, a type for the Virgin Mary, who instigates the blessing upon Jacob. It is Rebekah who takes the “best garments”of the first-born son Esau and “puts them on”the younger son Jacob, as the text reads: “Then Rebekah took the best garments of Esau her older son, which were with her in the house, and put them on Jacob her younger son.” (Gen. 27:15) It is Rebekah, behind the scenes, directing Jacob to put on Esau’s garments and receive the blessing of the father Isaac. Rebekah helps the quiet Jacob, who stays home with her, over the strong, self-serving hunter, Esau. St. Louis de Montfort equates Jacob with the righteous and Esau with the reprobate. In fulfillment of this typology, it is the Virgin Mary who comes to aid the faithful and devout Christian and clothes us with the garments of her Son, Jesus Christ, the first-born, in order to secure the blessing of God the Father and inherit eternal life. As St. Louis de Montfort wrote in True Devotion to Mary: “She clothes us in the clean, new, precious and perfumed garments of Esau the elder – that is, of Jesus Christ her Son – which she keeps in her house, that is, which she has in her own power, inasmuch as she is the treasurer and universal dispenser of the merits and virtues of her Son, which she gives and communicates to whom she will . . .” Just as Rebekah clothed Jacob with the finest garments of Esau to secure the blessing of Isaac the father, so too, does the Virgin Mary clothe us with the finest garments of Christ’s sanctifying grace in order to secure for us the blessing of God the Father for eternal life in Heaven.

St. Louis de Montfort calls Mary our “mediator with the Mediator.” The world, he says, is unworthy to receive directly from God himself so it receives grace through the intermediary of Mary, just as the world received the Incarnation of the Son, not directly, but through the intermediary of Mary. The Incarnation, and thus the Redemption, happened through Mary, and so, the on-going redemption of man continues to happen through the mediation of the Virgin Mary.

The life of Christ attests to her centrality too. Jesus lived in humble obedience in the house of Mary for thirty years! Think of that. He lived solely honoring his mother for the vast majority of his earthly life. This is the example par excellencefor us. If she was good enough for the Son of God to remain in humble obedience to for thirty years, surely we too should commit ourselves to honoring her. The angel Gabriel greeted Mary with the angelic salutation, “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women.” (Lk. 1:28) If Heaven greets Mary in such a way, as one full of grace and conceived without sin, surely we should invoke the Immaculate Virgin Mary in such a way too. The Annunciation is after all the moment of the Incarnation. In praying the Rosary, we are glorifying the work of God in the Incarnation. The Virgin Mary is the mother of the Incarnation and the Redemption. Mary points always to him. It is to Jesus through Mary, as she commands, “Do whatever he tells you.”

The beginning of Genesis frames the main struggle through history. The enmity that God speaks of in Genesis 3:15 is primarily between the serpent and “the woman.” The original woman, Eve, is another type for the second Eve, Mary. Adam and Eve were the original progenitors of humanity and source of Original Sin. Jesus and Mary are the spiritual progenitors of the children of God and the fixers of sin. In perfect symmetry, God wills the redemption of man through the new Adam, Jesus, and the new Eve, Mary. The sin of Eve is undone in the obedience of Mary. The first woman was instrumental in the fall, and the second woman is instrumental in the redemption. And, this redemption is ongoing. It is “the woman,” Mary who mediates Jesus’s first miracle at Cana, and it is “the woman” Mary, who Jesus entrusts the beloved Apostle John to from the Cross. The ancient enmity between the serpent and the woman reaches its final, apocalyptic climax in Revelation with “a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars” (Rev. 12:1) This is followed by the portent of “a great red dragon” whose head she will crush.

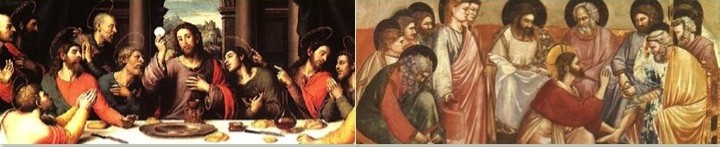

The enmity between the woman and the dragon is alluded to in the symbols of St. John Bosco’s prophetic dream of the two great columns: One great column has the Blessed Virgin Mary on the top of it, and on the other greater, taller column is the Blessed Sacrament of the Eucharist. The two great columns secure “the ship” of the Church under “waves” of attacks by the world, as he explained the vision, “Only two means are left to save her amidst so much confusion: devotion to Mary Most Holy and frequent Communion.” This seems more relevant now than ever before.