The Catholic faith is the reconciliation because it is the realization both of mythology and philosophy. It is a story and in that sense one of a hundred stories; only it is a true story.

-G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man

Christianity emerged out of the historical, social and religious milieu of first century Palestine. The area was a part of the Mediterranean world unified under Hellenic cultural influences and Roman military might. The pagan Roman populace had grown weary of their pantheon of gods and the seeming dreariness of everyday life. There was a spiritual hunger for something more, something transcendent. As the empire expanded its arms to the east and to the south so it also brought in elements from these foreign lands to the mainstream Mediterranean lifestyle. These imported elements included the so-called “mystery religions,” or “mysteries” to help satisfy this spiritual hunger. These mysteries included among others the cults of Mithra, Isis and Osiris, Dionysus, Magna Mater, and Cybele and Attis. Of these, perhaps the most prolific and influential was the Mithraic cult centered about the Persian deity Mithra. Mithraism, the most renown of the mysteries, has often been compared to Christianity. Many modern scholars argue that there are a number of striking similarities between Christianity, and the mysteries and Mithraism. Moreover, many such modern scholars have argued that not only has Christianity relied heavily upon the mysteries for its theology and practices, but also that Jesus himself is merely myth and Christianity just another mystery cult.

This paper will show the fact that Jesus was indeed a historical person and that Christianity was not just another mystery cult. On the one hand, Mithraism was a mystery based on the story of Mithra. On the other, Christianity grew out of Judaism and was based on the real person of Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, the two divergent groups did have some superficial similarities. These similarities have wrongfully been construed to “prove” that Christianity was dependent upon Mithraism and the other mysteries. This paper will then show on which points the groups diverge. It will show how the pagan mysteries evolved and blended their theology so as to imitate the rapidly rising Christian movement. Similarly, it will reaffirm the historical nature of Jesus Christ, and the uniqueness of the religion He began. Ultimately, it will reveal the fact that Christianity emerged from Judaism as a unique religious movement based upon the historical person of Jesus Christ, and that it was different from and in direct competition with the pagan mysteries and Mithraism.

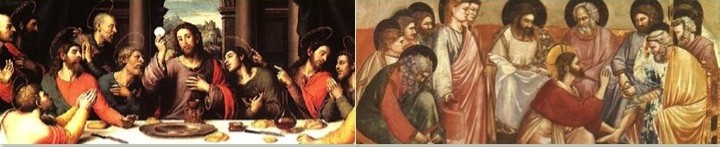

However, Christianity and Mithraism did have some apparent similarities that have been offered as proof of dependency. For example, the mysteries and Mithraism are considered religions of redemption similar to that of Christianity.1 The notion of a vicarious sacrifice for the sake of redeeming others seems to have been present. An inscription at the Mithraeum of Santa Prisca in Rome reads, “You saved us…by shedding the blood.”2 Mithra in effect saves his followers by reluctantly slaying the bull. Similarly, as Joseph Campbell points out, the mythology of dying and rising deities had been indigenous to the Near East for millennium.3 Mithra himself is the mediator, and also the god of light. He is born from a rock that was witnessed by on-looking shepherds similar to the birth of Christ. Mithra’s birth date is celebrated on December 25th. After killing the bull, Mithra then celebrates the love feast with his disciples at a “Last Supper.” At this last supper, Mithra offers an oblation of bread and a cup of water. After this he ascends into Heaven to be one with the Sun.4

Continuing in the teachings of Mithraism, at the end of the world there will be a resurrection of the dead in which Mithra will preside over the Final Judgment. Furthermore, Mithraism advocated an ascetic lifestyle. Life is a battle in that the initiate must struggle through the difficulties that may come. Abstinence was considered praiseworthy. They believed in Heaven and Hell and the immortality of the soul. The initiates went through a ritual washing of water, or “baptism” some would say. The initiates go through preparation and instruction and would be admitted into the mysteries in a nocturnal celebration on the eve of a great festival similar to the Christian catechumens entering the Church at the Easter vigil. Through an initiation process and ascending in the secret mysteries the person gains salvation. Many have compared these initiations and seven levels of Mithraism as a forerunner of the seven sacraments of the Church. Taking in all of these apparently close parallels between Christianity and the mysteries and Mithraism, many have concluded that Christianity is but myth and itself a mystery cult. As one author noted.

The obvious explanation is that as early Christianity became the dominant power in the previously pagan world, popular motifs from Pagan mythology became grafted into the biography of Jesus.5 The Christian Bible and historical Jesus at best would have just blended some aspects of the pagan mysteries into the true facts. At worst, the Bible and Jesus were pure legend in line with the Mithraism and the other mysteries.6

Despite these similar portraits between Christianity and the Mithraism, significant differences do exist. First off, just looking at the origins of the two competing religious movements reveals an abundance of dissimilarities. Mithraism was a cult based upon astronomy and astrology.7 Of course, astrology and soothsaying was explicitly condemned in the Bible.8 The initiates were to ascend through the seven spheres of the heavens. The Mithraic caves, or Mithraeums, where the ceremonies were held, were covered in a depiction of the zodiac mirroring the cosmos. Moreover, most Mithraeums had iconography of the Mithraic tauroctony. This key icon showed Mithras standing over the bull and slaying it. Given the complete astronomical orientation of the cult, as David Ulansey argues, Mithras in the iconography is actually the constellation “Perseus.” Seen from this perspective, the tauroctony was actually a “star map.”

As Ulansey argues, Mithraism was developed by Stoic philosophers in the city of Tarsus. The Stoics were philosophers steeped in astronomy and astrology. They had learned at the time of a revolutionary idea discovered by Hipparchus about the procession of equinoxes. Thus, they reasoned there must have been a great god who could have shifted the whole cosmos from the end of the age of Taurus. With Perseus directly above Taurus in sky, the Stoics then actually personified the constellation as their local hero, Perseus. Later, Cilician pirates, who themselves navigated by the stars and who had close contact with the wealthy and intellectuals, adopted the cult and changed the god from the Tarsus hero, Perseus, to Mithra. As testified by Plutarch, they then helped spread the new astrological cult of Mithra around the empire.9 Thus, the Persian myth of Mithra was superimposed upon the new astrological cult of Perseus begun originally by Stoics of Tarsus to account for the astronomical discovery of the procession of equinoxes.10

Because the Stoics are from Tarsus, the city St. Paul was from as well, many attribute Paul’s religion as just another mystery and one influenced in particular by Mithraism. This is an impossibility given what we know of Paul. Paul was a strict Pharisaic Jew schooled under Rabbi Gamaliel. In addition, there is no historical evidence that paganism had entered into the common life of the Jews.11 Paul was interested solely in preserving the Mosaic Law and strictly adhering to every letter of it. This can be witnessed in his early persecution of the nascent Church. Paul voiced the same abhorrence later for paganism. As he states in his letter to the Corinthians warning them about the dangers of idolatry and paganism, “You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and also the cup of demons.”12 In addition, Paul had extended contacts with the Apostles themselves. The Church in Tarsus was in effect the same as the Church in Jerusalem. Both, as one Church, held that to be Christian meant renunciation of all other “gods” and idolatrous practices. Moreover, the New Testament canon is clearly supported by Old Testament scriptures and prophecies. As such, Paul advocated belief in Christ alone. Christianity, like Judaism, was completely intolerant of any other religions. Paul’s religion was exclusive while the mysteries were merely one of many interchangeable myths. It is very difficult indeed to imagine that this same Paul with his zealous orthodox Jewish beliefs was susceptible to pagan influences and Mithraism.

Furthermore, the Mithraic practices differed widely with those of Christianity. To begin with, whereas Christianity was open to all, Mithraism was open only to men. Women were not allowed into the cult. Of the hundreds of Mithraic inscriptions none include that of a priestess or a woman initiate.13 Mithraism was in general a soldiers and merchants religion.14 The cult spread mostly through the Roman legions. The cult was highly personal and individualistic. In this sense Mithraism was not a religion at all. The very term “Mithracists” is a modern phrase not found in ancient literature.15 There was no sense of community, organization or solidarity.16 The pagan mysteries had no sense or equivalent of the ekklesia. There was no concern for the poor; no economic cooperation; no inclusion of the family unit. Many pagans converted, such as Tatian and Justin, for the very fact that they saw the hospitality that Christians treated each other with saying, “Look how they love one another!”17 The total inclusion and submission of family into a community of believers is ridiculous when applied to the mysteries.

Christianity from its inception, however, was focused on the community of believers as the body of Christ. Christianity was a public religion open to all. The “mystery” as referred to by Paul and the New Testament is used as some as proof by terminology of Christian dependence upon the mysteries. Yet, the whole point of the “mystery” of Mithraism and the other cults was to keep all knowledge secret. The secrets of the mysteries were to be known only by the initiates, again alluding to the highly individualistic nature of the mysteries. In Christianity, however, “mystery” was something that was previously hidden in the mind of God, but now has been revealed and is to be made known to all.18 Thus, unlike Mithraism and the mysteries, Christianity was at once dogmatically intolerant of other faiths, yet it was open to any and all people. Christianity was preached everywhere openly, while Mithraism was kept secret known only to the initiates.19 In this vein of secrecy, it is not surprising that although there is an abundance of archeological evidence of Mithraism, there are almost no literary references to it.20 Since it was a secret society of sorts, none of its dogmas or tenets were written down. What is known of the cult is solely through iconography.21 This, of course, is in complete contradiction to the comparatively copious amounts of writings from the New Testament and the early church Fathers.

In connection with these differences, Tertullian offers some first hand accounts. Tertullian was an eyewitness to the Roman soldiers and the Mithraism in their ranks. He says that Mithraism attempted to copy Christianity.22 Tertullian writing in the latter second century says that Mithraism, and by association military life, was incompatible with Christianity. Firstly, Roman legions were often followed by prostitutes, pimps, gamblers and con-men.23 He also speaks of the idolatry involved in serving in the military through sacrifices and capital punishment. In his Treatise on the Crown Tertullian says,

Blush, you fellow-soldiers of his, henceforth not to be condemned even by him, but by some soldier of Mithras, who, at his initiation in the gloomy cavern, in the camp, it may well be said, of darkness, when at the sword’s point a crown is presented to him, as though in mimicry of martyrdom,…and he is at once believed to be a soldier of Mithras if he throws the crown away – if he says that in his god he has his crown. Let us take note of the devices of the devil, who is wont to ape some of God’s things with no other design than, by the faithfulness of his servants, to put us to shame, and to condemn us.24

So, just as Christians who refused to wear the crown of the king were executed, so too the Mithraic soldiers mimicked that faithfulness in their initiation ceremonies. Yet, Tertuallian describes Mithraism as the “device of the devil,” and in contrast to Christianity, something that is shameful and to be condemned. Thus, Tertullian quotes Jesus in admonishing Christians in the military that they “can’t serve two masters.”

Yet, again this exclusiveness of Christianity was not found in the mysteries. Mithraism was completely acceptable with other forms of paganism and even emperor worship. As Tiridates, king of Armenia, came to Rome on a state visit he is quoted as saying, “I have come to you, my god, to worship you as I worship Mithras.”25 Moreover, many Mithraicists were involved in more than one mystery. One could easily have been initiated into Mithraism without giving up his beliefs in say, Isis.26 The fluidity of the myths of the mysteries made them increasingly popular, especially by the end of the second century. It was at this point that Mithraism in particular became one of the favorites of the Roman aristocracy.27 Even the emperor Commodus who ruled from 180-192 AD was initiated into Mithraism which reflected a triumph of the cult.28 As one author noted the inclusive nature of the mysteries,

Thus, the use of the term “mystery religions,” as a pervasive and exclusive name for a closed system, is inappropriate. Mystery initiations were an optional activity within a polytheistic religion, comparable to, say, a pilgrimmage to Santiago di Compostela within the Christian system.29

These mysteries in general had some very foreign, and even, hedonistic rites in comparison to Christianity. Gregory of Nazianzus spoke of various tortures and humiliations involved in the Mithraic initiations.30 Other mysteries’ initiation rites included drugs and orgies. In some initiation rites they practiced the “taurobolium.” The taurobolium consisted of the initiate crouching in a pit covered in wooden beams on which a bull was slaughtered and the person was covered in its blood.31 This was a primitive practice adopted to give the initiate an “emotional high.” The Christian notion of a vicarious and voluntary suffering for others is not found in the mysteries, especially in Mithraism. Moreover, the “suffering god” myth is completely absent from Mithraism.32 Even more obvious, this form of animal sacrifice was not present in Christian practices. There was in Mithraism in particular a reduction of practices to the physical. For example, they would eat the raw flesh of the sacrificed bull.33 The notion of spiritual things or a spiritual communion as in Christianity was totally lacking in the mysteries. Salvation is seen more as a “magical liberation from the flesh,” than as the redemption from sin.34

There were other practices as well. As far as December 25th as the birth of Mithras and of Christ, it can be said that Constantine had in fact changed the celebration in 323 AD from the birth of the Sun, Mithras, to Jesus.35 In addition, Augustine writing some time later spoke of the Mithraic initiates as “flapping their wings like birds, imitating the cry of crows, others growl like lions, in such a manner are they that are called wise basely travestied.”36 These practices were in correspondence to the seven levels of initiation. Even these seven levels of initiation were not found in Christianity. There was also a “sprinkling of water” the Mithraicists used. Modern liberal scholars have anachronistically dubbed it a “baptism” using the Christian terminology. Of course, there is truly no evidence for a Mithraic baptism, especially one that was a symbol by emersion in water of dying and entering into a new life as in the Christian rite.37 Similarly, the modern liberal scholars have also dubbed the Mithraic feast a “Last Supper,” again imposing the Christian terminology. The “Mithra supper” involved bread and a cup of water. So, in this case, it was not bread and wine, and they did not become the “body and blood” of their “god.” Thomas Bokenkotter points out that even these similarities don’t necessarily indicate dependency. As he suggests, “Such primitive symbols are so basic to humanity that any religious person might use them to express an experience transcending this world.”38

What perhaps is much more interesting is the fact that the early Church Fathers all seem to agree that Mithraism had attempted to copy Christianity. It seems the most logical conclusion that Mithraism, in fact, tried to imitate the increasingly popular Christian religion. St. Justin had argued that the devil had foreseen the coming of Christ and Christianity, and so, he mimicked Christianity and the divine sacraments.39 Tertullian had argued as well that the devil had directly tried to copy Christianity.40 He also suggests that the soldiers were not really astute theologians so they tended to blend Christianity and Mithraism.41 Perhaps this is a large part of the reason why there could have been similarities between the two “religions.” Looking at the two divergent faiths, it is not difficult to see the evolution in teachings. Christianity, on the one hand, sprang forth from a strictly Judaic background. The Christian adherent had to renounce all other gods and idolatrous practices. As attested to by the Christian martyrs, no compromise was possible. On the other hand, there are the mysteries and Mithraism. By their very nature, they were all-inclusive. No one need reject their other gods or other beliefs to participate. Mithraism in particular was very fluid and adapted through time. This is evident looking back to the Mithraism of ancient Persia from which it came. The Roman Mithraism was an almost completely different religion from its origin. It had become, as Cumont depicted it, a “composite religion, in which so many heterogeneous elements were welded together.”42 Mithraism specifically attempted to establish its own superiority through a succession of adaptations and compromises with the other pagan mysteries.43 For example, Julian the Apostate tried to establish a universal pagan Church using a clergy and liturgy based on the Christian model.44 Christianity, however, unrelentingly fought against any compromises with paganism. As Cumont surmised,

Mithraism, at least in the fourth century, had therefore as its end and aim the union of all gods and all myths in a vast synthesis, the foundation of a new religion in harmony with the prevailing philosophy and constitution of the empire.45 In contrast, the direct Christian abhorrence to the mystery religions can be seen in Hippolytus’ condemnation of Gnostic sects for their dependence upon the mysteries! 46

It seems that Mithraism in its hopes for universal domination imitated and synthesized the beliefs and practices of the rising and increasingly popular Christianity in order to stay on pace with it. This dependency then of Mithraism upon Christianity can be seen too in the archeological evidence, or lack thereof. The characteristics of Mithraism are not in evidence truly before the year 100 AD.47 As Cumont described it, it was not until the end of the first century that “the name of Mithra began to be generally bruited abroad in Rome.”48 In fact, the earliest known reference to Mithraism is from around 80 AD.49

Mithraism reached the peak of its power around the middle of the third century while Christianity was still being brutalized.50 This again attests not only to the late date of Mithraism, but also to the hostility between the two creeds. Most of the evidence of Mithraism and the mysteries comes from after the year 200AD.51 Modern liberal scholars have tended to extrapolate from this late evidence, and then, to erroneously confer dependency of Christianity upon Mithraism. Moreover, there are no monuments of Mithraism before 90AD.52 Thus, it is clear that the flowering of Mithraism took place truly after the establishment of the Christian church and the writings of the New Testament canon. As Gunter Wagner summarized it, “Moreover, on account of the lateness of its spread, there is no question of the Mithras cult influencing primitive Christianity.”53

Now, perhaps the greatest dissimilarity between Mithraism, the mysteries, and Christianity, and perhaps the most obvious, was simply that they were myth and Christianity was historical. The fact remains that there never existed a historical person Mithra. He was an invention of man, a myth. On the other hand, Jesus Christ clearly was a historical person, not a myth. Mithraism, like the other mysteries, was a timeless myth intimately linked to the rhythm of nature of death and rebirth. Jesus Christ was a historical person with datable events. As Cumont saw it, “It was a strong source of inferiority for the Mazdaism (Mithraism) that it believed in only a mythical redeemer.”54 Paul in his writings is more than anything else a witness to the person of Jesus Christ. The New Testament books and epistles are almost all written before the close of the first century, and as such, should be counted as historical evidence to the person of Jesus of Nazareth. There were also some limited extra-biblical references to the person of Jesus and Christians. There is an abundance of second century Christian writings to substantiate this, such as from Iraeneus, Ignatius, Polycarp, Clement, Justin, Hippolytus, some of who had contact with the Apostle John.

As for the non-Christian writings there is some evidence as well. There were Roman historians at the beginning of the second century who referred directly to Christ. Pliny the Younger wrote a letter to the emperor Trajan in the year 112. An excerpt states, “..on a fixed day they used to meet before dawn and sing hymns to Christ, as though he were a god.”55 Suetonius writes that “Punishment by Nero was inflicted on the Christians..”56 More provocatively, the Roman historian Tacitus writes about the burning of Rome under Nero in 64AD that,

..he falsely charged with the guilt, and punished with the most exquisite tortures, the persons commonly called Christians. Christus, the founder of the name, was put to death by Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judea in the reign of Tiberius..57

Lucian of Samosata, a second century satirist writes “..the man who was crucified in Palestine because he introduced this new cult into the world..”58 Suetonius, another Roman historian writes about the Christians, “Punishment by Nero was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous superstition.”59 Julius Africanus, a Christian writer of about 221 AD refers to a writing by the pagan historian Thallus in 52 AD saying that the sun was eclipsed at the time of Christ’s crucifixion.60

There were also a few references to Christ by Jewish sources, in particular, the historian, Flavius Josephus. Although some dispute the text, and there probably were some later Christian additions to it, there is no reason to throw out the whole reference. Josephus, who was a contemporary to Jesus, wrote (from the unadulterated Arabic text),

At this time there was a wise man who was called Jesus. And his conduct was good, and he was known to be virtuous. And many people from among the Jews and the other nations became his disciples. Pilate condemned him to be crucified and to die. And those who had become his disciples did not abandon his discipleship. They reported that he had appeared to them three days after his crucifixion and that he was alive;61

Josephus also later refers to the Apostle James saying, “..and brought before it the brother of Jesus the so-called Christ, whose name was James..”62 Similarly, the Jewish Talmud, which clearly are not Christian forgeries, also mentions Jesus. One reference among a few of them states, “It has been taught: On the eve of Passover they hanged Yeshua…because he practiced sorcery and enticed Israel astray.”63

Therefore, although there are some similarities between Christianity and Mithraism and the mysteries, there are greater differences. The evidence indicates that Mithraism was dependent upon Christianity, not visa versa. Mithraism in particular was an astrological cult that would not have fit well with Christianity, and particularly, Paul’s condemnation of pagan practices. Mithraism was open only to men and was mainly a soldiers and merchants religion. Christianity was open to all. At the same time, initiates in Mithraism could freely participate in other religious cults, whereas the Christian catechumen had to renounce all gods and idols. Mithraism mystery was based on secrecy, and as such, no literary works have been recovered. Christianity’s mystery was to be proclaimed to the world, and as such, many Christian writings on doctrines and dogmas exist. The theologies of the two seem to vary on substance. Modern liberal scholars often times wrongfully apply Christian terminology to Mitrhaic practices lending to the idea of a greater similarity than actually existed. Mithra was not even a dying and rising god, and so, the “suffering god” myth does not even apply. Furthermore, there is no historical or archeological evidence that Mithraism in its Roman version preceded Christianity. The New Testament canon was already complete by the rise of Mithraism. Mithraism was based purely on myth while Christianity was based on the historical person of Jesus Christ. There are biblical and Christian, Roman, and Jewish extra-biblical writings to support the historical person of Jesus and Christianity.

The conclusion must be that through adaptations and synthesizing aspects of various cults and religions, Mithraism evolved from its Persian origins into a pagan Roman mystery cult. Christianity, on the other hand, stubbornly refused to give into any pagan influences or idolatry. Despite being forced to endure over three hundred years of persecutions and martyrdom, the Church continued to grow and thrive. Quite the opposite was true of Mithraism and the mysteries. They continued to import and meld together aspects of pagan practices, eastern myths, and Christianity for public consumption. The Mithraic cult’s ultimate aspiration was to rule the empire and to impose Mithras as the greatest of the gods. However, as Beckert describes it, “..with the imperial decree of 391/392 AD prohibiting all pagan cults and with the forceful destruction of the sanctuaries, the mysteries simply and suddenly disappeared.”64 Thus, as soon as Mithraism lost state protection the whole structure crumbled. In contrast, it is nearly unbelievable that Christianity rose from humble and victimized beginnings to become against all odds the state religion of the Roman Empire.

1Walter Burkert, Ancient Mystery Cults, (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1987), p.3.

2Ibid, p.112.

3Joseph Campbell, Occidental Mythology,(Viking Penguin, New York, 1964), p.334.

4Burkert, p.138.

5Timothy Freke & Peter Gandy, The Jesus Mysteries, (New York, Harmony Books, 1999), p.6.

6Burkert, p.190.

7David Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries, New York, Oxford Univ.Press, 1989, p.93.

8Deuteronomy 18:10

9 Ulansey, p.40.

10Ibid., p.93.

11J.Gresham Machen, D.D, The Origin of Paul’s Religion, New York, The MacMillan Co., 1921, p.255.

121 Corinthians 10:21.

13Franz Cumont, The Mysteries of Mithra, New York, Dover Publications, 1903, p.173.

14Burkert, p.7.

15Ibid., p.47.

16Ibid., p.48.

17Thomas Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church, New York, Double Day, 1979, p.26.

18Machen, p.273.

19Bokenkotter, p.24.

20Burkert, p.42.

21Ulansey, p.6.

22Robert Day, et al., Christians and the Military: The Early Experience, Philadelphia, Fortress Press, 1985, p.25.

23Day, p. 49.

24Tertullian as quoted by Day in Christians and the Military, p.29.

25Jack Finnegan, Myth and Mystery, Grand Rapids, MI, Baker Book House, 1989, p.205.

26Machen, p.9.

27Cumont, p.81.

28Ibid., p.97.

29Burkert, p.10.

30Ibid., p.102.

31Ibid., p.6.

32Ibid., p.76.

33Ibid., p.110.

34Bokenkotter, p.25.

35Finnegan, p.208.

36Cumont, p.152.

37Burkert, p.101.

38Bokenkotter, p.25.

39Johannes Quasten, Patrology: Volume I, Westminster, MD, Christian Classics, 1990, p.200.

40Freke, p.28.

41Day et al., Christians and the Military, p.25.

42Cumont, p.30.

43Ibid., p.197.

44Fr. John Laux, Church History, Rockford, IL, Tan Books and Publishers, Inc., 1930, p.97.

45Cumont, p.187.

46Machen, p.249.

47Burkert, p.7.

48Cumont, p.37.

49Ulansey, p.29.

50Cumont, p.199.

51Dr. Ronald H. Nash, “Was the New Testament Influenced by Pagan Religions?,” 1994, p.3, accessed 11/15/00, (www.summit.org),

52Ibid., p.5.

53Gunter Wagner, Pauline Baptism and the Pagan Mysteries, Edinburgh, Oliver & Boyd, 1967, p.68.

54Cumont, p.195.

55Laux, p.52.

56Josh McDowell, Evidence that Demands a Verdict, San Bernadino, Here’s Life Publishers, 1972, p.83.

57Ibid., p.82.

58Ibid.

59Ibid.

60Ibid.

61Ibid., p.82.

62Ibid., p.83.

63The Jewish Talmud as quoted Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy in The Jesus Mysteries, p.138.